Carnot heat engines and reversibility

The second law of thermodynamics is one of my favorite “laws” of physics because of its immense implications for our universe (e.g., the arrow of time) and also because it is so simple to state (e.g., one way to state the second law is: “It is impossible for heat to spontaneously, without requiring external work to be supplied, flow from a cooler body to a warmer body”), yet so many surprising implications flow from it. In that way, it is similar to group theory, where just three axioms lead to a beautiful and intricate theory that enables us to rigorously think about the symmetries of the universe.

When we first take a course on thermodynamics and learn about the second law, we usually hear about the very surprising consequence that all reversible heat engines, utlizing heat from two thermal reservoirs with specified temperatures, have the same efficiency. In other words, given that there are two temperatures and that there is a heat engine that can use reservoirs at those two temperaratures to generate work, and given that the heat engine is reversible (meaning that it is perfectly lossless), it MUST have the same efficiency as all other possible reversible heat engines that operate at those two temperatures. No matter how the reversible heat engine is designed, what materials are used to construct it, and how exactly it is operated.

And we learn that this is proven by contradiction: if we were to assume that there exists two reversible heat engines with different efficiencies, then that would lead to contradictions with various statements of the second law:

- Heat cannot, of itself, flow from a cold to a hot object

- It is impossible to devise a cyclically operating device, the sole effect of which is to absorb energy in the form of heat from a single thermal reservoir and to deliver an equivalent amount of work

I’ve always felt some sense of wonder at this, as if I just witnessed a magician perform some sleight of hand. A bunch of heat engines running forwards and backwards, heat flows, work is performed, and poof, the magical conclusion is proven. Why is this possible? Is there something special about heat engines? Or about the second law? What’s going on under the hood, mathematically?

The good news is that it’s actually very simple to understand why this must be so.

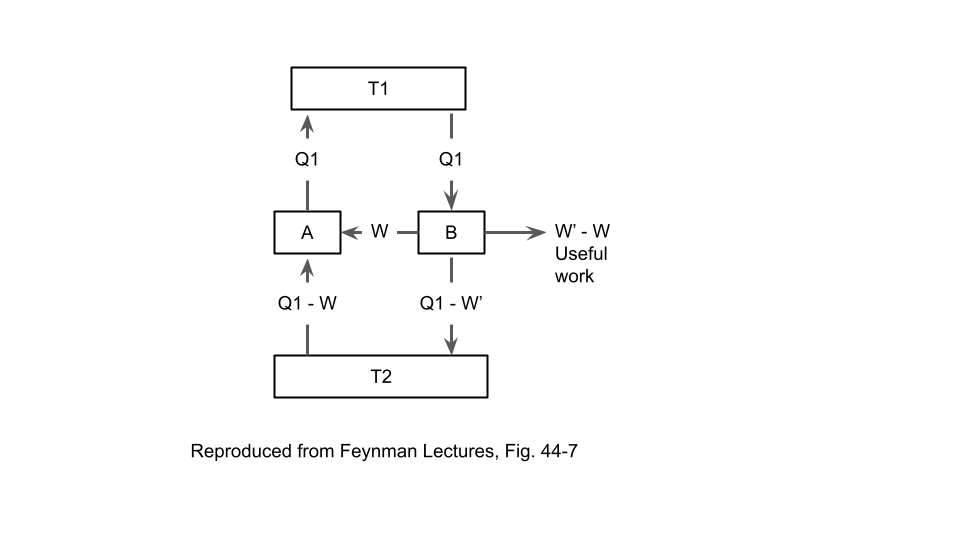

Consider a generic reversible heat engine. It has two heat flows that connect to two thermal reservoirs and one work output (which could be negative, if work is performed on the heat engine by an external source). Conservation of energy requires that the sum of these three must be zero (although we do need to be careful and consistently pick the positive directions for the three quantities). Now, consider two different reversible heat engines \(A\) and \(B\) connected in parallel, so that both heat engines have heat flows connected to the two thermal reservoirs. This will look similar to the diagram above.

Now, assume that the two engines are running in opposite direction. For example, let’s say that \(A\) is drawing heat from \(T_1\), expelling heat into \(T_2\), and producing positive work output; and let’s say that \(B\) is doing the reverse. Now consider the combination of the two heat engines as a black box that has:

- A total heat flow connected to \(T_1\)

- A total heat flow connected to \(T_2\)

- A total work output going to the external world

So there are 3 quantities to consider for this black box. Let’s ask this question: What if one or more of those quantities is zero?

From conservation of energy, we know that if two of the quantities are zero, then the third is zero also. We then have an exact cancellation of the two heat engines, and they are identical in efficiency but just running in opposite directions. Not very exciting.

If exactly one of the quantities is zero, then that quantity is either a heat quantity (connected to one of the reservoirs) or a work quantity (connected to the external world). If a heat quantity is zero but the work quantity is nonzero, that is equivalent to having different efficiencies for the two heat engines. They are drawing/expelling the same magnitudes of heat from one of the reservoirs, yet the magnitudes of work produced are different and not cancelling to zero work. And we are led to the conclusion that we would be able to produce work while using only a single thermal reservoir, which is a contradiction of the second law.

If the work quantity is zero but the two heat quantities are nonzero, that means that the two heat engines are producing/consuming the same amount of work but in opposite directions, and moving different magnitudes of heat from the two reservoirs so that the heat quantities are not cancelling out. So again, this means that the two heat engines have different efficiencies. This would imply that we have a net quantity of heat moving from one reservoir to another reservoir, at two different temperatures, without any external work. And because the heat engines are reversible, we could also have a situation where heat is moving between the two reservoirs in the opposite direction, again without external work. One of these two situations will imply that we can cause heat to spontaneously, without requiring external work to be supplied, flow from a cooler body to a warmer body; and this would be a contradiction of the second law.