The second law of thermodynamics and why entropy must increase!

The second law of thermodynamics is one of the most interesting “laws” of physics. Among all our physical theories, the second law of thermodynamics is thought to be the most likely to withstand the test of time. Other key theories such as classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, special relativity, and general relativity, are either known or suspected to be incomplete in some way, and the expectation is that future scientists will come up with more complete theories that better describe the known empirical data. This is because their foundational assumptions lead to incomplete explanations of our world. To give a few examples: non-relativistic quantum mechanics does not handle the symmetry between space and time; and general relativity seems incomplete because it gives rise to mathematical singularities that do not seem physical. So they have fundamental issues at the foundation.

The “second law,” however, seems different. The wikipedia article on the second law has this nice quote:

The law that entropy always increases holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell’s equations – then so much the worse for Maxwell’s equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation – well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. — Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

One interesting aspect of the second law is the diversity of how it can be stated. In the Wikipedia article above, there is a complete section on some of the most prominent statements of the second law and how they relate to each other. It is striking how some of the statements, such as Carnot’s principle, seem so explicitly grounded in experimental measurements of heat engines, while other statements, such as the one from Uhlenbeck and Ford, involve abstract concepts such as entropy. So here in this post, I would like to show how Carnot’s principle implies the statement from Uhlenbeck and Ford.

We recall the fact that the path integral of \(\delta Q / T\) around a Carnot cycle is zero (see my prior post). This means that if you take a reversible heat engine that goes through a complete Carnot cycle between two temperatures (call them \(T_H\) and \(T_L\)) and divide its state space path into very small steps, each step would involve an inflow \(\delta Q\) of heat into the engine at a temperature \(T\), and the path integral around the complete cycle is zero. Remember this for now, and we will come back to it at the end of the post when we talk about entropy.

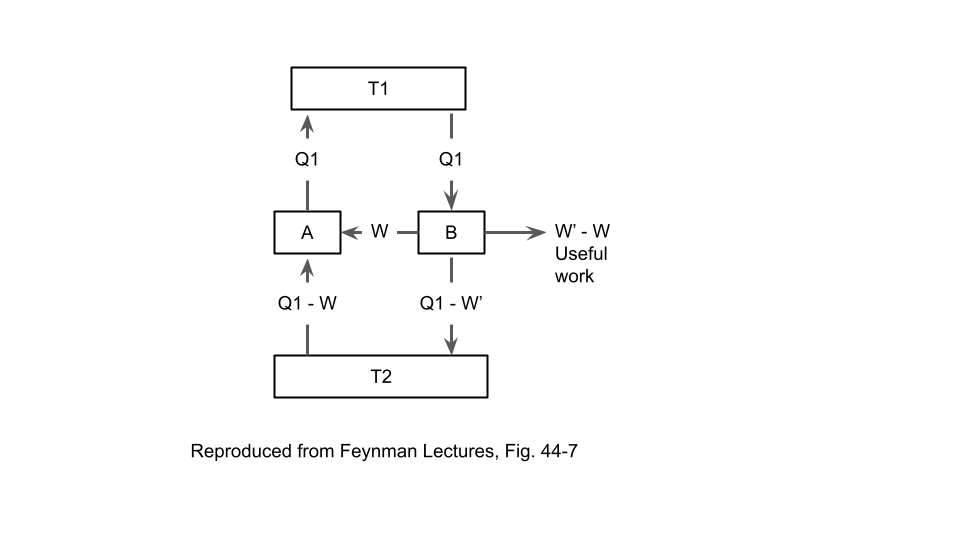

Suppose that we have a second heat engine that is identically constructed and is operated in an identical fashion, except for one small part: at one of those small steps at the higher temperature \(T_H\), the second engine follows an irreversible process. What is the meaning of this? It means for that specific step (for clarity, we will refer to this as the STEP), the second engine will begin and end at the same points in state space as the first engine (the first engine = the Carnot engine), but it moves between those two state space points in a way that is irreversible. Except for the STEP, the second engine is exactly the same as the first engine throughout the rest of the state space path.

The second engine is not a reversible engine because it has an irreversible portion. So now we can start with Carnot’s principle, which is his statement of the second law that a heat engine operating between two temperatures can be no more efficient than a reversible Carnot engine (my prior post gives some more background on this). This implies that the second engine must have a lower efficiency than the first engine, which makes intuitive sense because the second engine is incurring some loss or wasted energy during the irreversible part of its operation.

For the first engine, a reversible Carnot engine, let the heat flow during the STEP be \(\delta Q_{Rev}\), where “Rev” means that this is a reversible step. For the second engine, let the heat flow during the STEP be \(\delta Q_{Irrev}\), where “Irrev” means that this is an irreversible step.

Now, a heat engine with higher efficiency would draw in more heat \(Q_H\) at the high temperature and/or expel less heat \(Q_L\) at the low temperature because that would mean a larger fraction of \(Q_H\) is being converted to work. Therefore, since the two engines expel the same amount of heat \(Q_L\) at the low temperature, and since we know the second engine must be less efficient, we conclude that the second engine must draw in less heat at the high temperature. So this means that:

\[\delta Q_{Irrev} < \delta Q_{Rev}\]Next, we go back to the fact that the path integral of \(\delta Q / T\) for the first engine (a reversible Carnot engine) around its cycle is zero. This means that \(\delta Q / T\) is the perfect differential of a state variable, and we define that state variable as the entropy \(S\), so that \(dS = \delta Q / T\) (see this prior post for more details).

Since the entropy \(S\) is a state variable that is uniquely defined for every point in state space, the change in entropy over the STEP must depend only on the starting and ending points in state space for the STEP. And since both engines take the STEP with the same sets of starting and ending points in state space (even though one engine goes through a reversible process and the other engine goes through an irreversible process), the change in entropy over the STEP for the second engine is the same as the change in entropy of the first engine! We denote that change in entropy as \(\delta S\).

So for the first engine, since it is a reversible engine, its increase in entropy of \(\delta S\) must be counterbalanced by an opposite change in entropy of \(-\delta S\) in the temperature reservoir at \(T_H\). This is required because the change in total entropy for the whole system (reservoir plus engine) for a reversible process is zero.

And for the second engine, because its heat inflow \(Q_{Irrev}\) during the STEP is smaller compared to \(Q_{Rev}\) for the first engine, the change in entropy of the temperature reservoir must be a smaller drop, which means that at the system level the entropy increase in the second heat engine (which is the same \(\delta S\) as the first engine, as we showed above) will dominate over the entropy decrease in the reservoir, and therefore the total entropy for the whole system will INCREASE.

And so we arrive at the statement from Uhlenbeck and Ford of the second law of thermodynamics:

… in an irreversible or spontaneous change from one equilibrium state to another … the entropy always increases.